With the revival of trade routes and trade in the Middle Ages, Finisterre Cape regained its crucial role as a reference for navigators, being one of the three most dangerous capes that could not be beat in the crossings between Northern Europe and the Mediterranean, Together with those of San Vicente (Portugal) and Raz de Ouessant (Brittany).

In the 16th century, a new dimension emerged because of its role as a landing point for ships arriving from America to Europe, surpassing the framework of coastal navigation. At the same time, the routes that reached Finisterre by land as an extension of the Jacobean Way were also important.

Good reference of its transcendence is the magnitude of the maritime traffic registered in the middle of century XIX. Only for a year had they passed 3097 ships there.

With this background, the General Plan of Maritime Lighting of 1847 pointed out Finisterre Cape as a site for a large first-class lighthouse, whose project commissioned Félix Uhagón, who had already carried out the projects of the lighthouse Machichaco and Estaca de Bares.

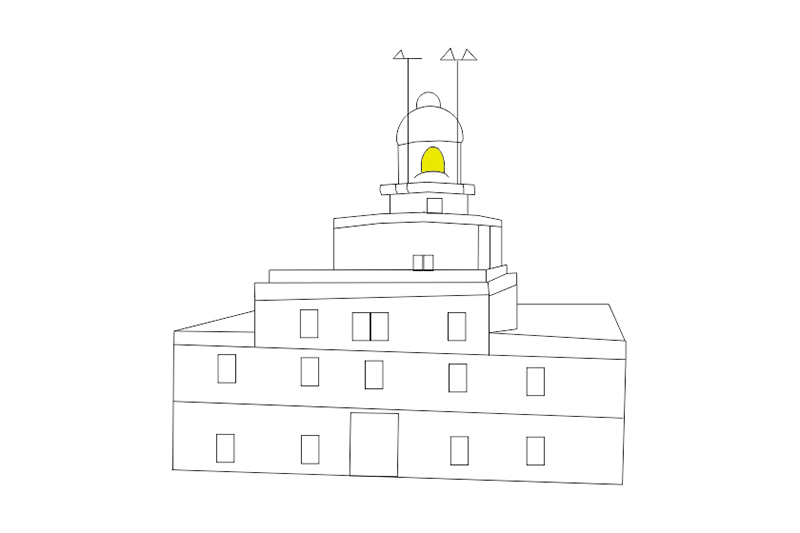

The current building was inaugurated in 1853 being the oldest of Coast of Death. It is a lighthouse of the first order and since 1931 it is electrified. The tower, 17 meters high, is octagonal and its current range is about 23 miles.

Curiosities, myths and legends

From La Nave Cape to Finisterre Cape, there are a series of restingas and reefs more or less distant from the coast that cause a very difficult stretch and that were the cause of many accidents: "A Carraca", "O Petón Mañoto", "O Centolo" "O Socabo", "The Wall", "O Petonciño" ... All this rosary of stones that really are granite octopi, whose tentacles go to the same shore.

Among all those stones, the most popular is the Centolo. At less than seven hundred meters badly measured from Punta da Puntela, the Centolo has a bad sign, since there have been numerous and tragic events happened being the most relevant the shipwreck of "The HMS Captain" in 1872 with 482 dead.